Andy Harmer

Andy Harmer Natural England

Natural EnglandDrones have been buzzing over Welsh wetlands this year as researchers try to find curlew nests and save the upland wader from extinction.

The Eurasian curlew could be gone in Wales as a “viable breeding species” by 2033 if a 6% annual decline continues, experts warn.

The thermal imagine drones spot heat from nests hidden in deep grass and bogs.

Electric fencing, as well as fox and crow culls, can then be used to protect the curlew’s chicks.

“If we don’t start doing it now, it’s going to be too late,” said Tony Cross, an ornithology consultant working with Natural Resources Wales (NRW) on a curlew recovery plan.

It cites habitat loss, farming practices and predation as the main pressures on an estimated breeding population of between 400 and 1,700 birds, down by up to 90% in the past three decades.

He said it would be “horrifying” to lose “that evocative, bubbling call up in the hills”, describing it as a “symbol of wilderness”.

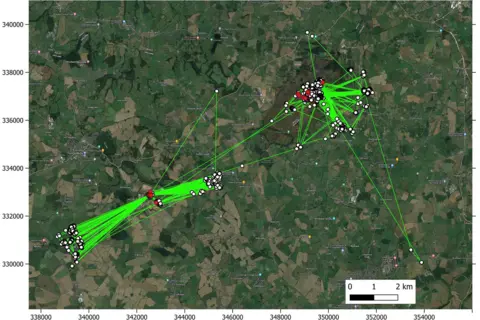

Mr Cross added technology was helping, including a “massive advance” in GPS trackers, which are now small enough to “strap on the back of a curlew”.

NRW fitted 15 curlew in Wales with GPS tags in 2022, giving researchers a real-time view of their migration from across Europe to important breeding and wintering areas in Wales.

The most recent data shows seven birds returned to Wales this year – six to breed after wintering in Ireland and one that bred in Sweden but wintered on the Dyfi Estuary near Aberystwyth in Ceredigion.

One place the Welsh curlews came back to this year was near Fenn’s, Whixall & Bettisfield Mosses, a nature reserve straddling the Wales-England border near Wrexham.

Bea Eade helped to set up electric fences in the reserve to try to protect the young from predators.

“I saw my first ever curlew yesterday and it was quite special,” she said.

“It would be a shame if future generations didn’t have that,” the 19-year-old from Telford in Shropshire added, describing the bird’s curved beak as “cute”.

Daniel Johnson, 22, from Wem in Shropshire, is also volunteering to try and help save the curlew.

“It’s important for people to know that this beautiful species that is quite iconic in Wales is under threat,” he said.

“I really hope my children and grandchildren will be able to see them.”

How to save the curlew?

One in six of the nearly 4,000 animal, plant and fungi species in Wales face extinction, with the curlew described as the country’s “most pressing bird conservation priority”.

The decline of their natural habitat means curlew often breed in farmers’ hayfields where their nests can be destroyed if the grass is mown in May or June, before chicks have had time to fledge.

“The thing we have to get right in the next decade is integrating curlews with farming,” Mr Cross said, suggesting a new agricultural subsidy deal that rewards farmers for protecting curlew habitats.

But wildlife habitat measures in the Welsh government’s Sustainable Farming Scheme were widely criticised by farmers and the scheme has been delayed until 2026.

Farmers who want to help curlew on their land now face the same problem as researchers – their nests are notoriously difficult to find.

The bird has a long history in Welsh folklore.

St Beuno, a seventh century abbot, was said to be so grateful to a curlew for rescuing his prayer book after it fell into the sea that he asked for all curlews to be protected.

“Now we have the benefit of modern technology to help us identify those nests a little more easily,” said Bethan Beech, from NRW, adding that their nests give off heat, which is visible to thermal imaging cameras.

Ms Beech is leading curlew recovery projects in 12 locations across Wales, including near Whixall where NRW and Natural England are using drones as part of a nest-finding trial.

She said locating breeding sites could help researchers find out where the birds are, as well as “how many chicks they are likely to be producing”.

Researchers can also put electric fencing around the nests to keep out predators and pinpoint the best places to reduce fox and crow numbers by culling.

Tony Cross

Tony CrossDrones could one day be used to help farmers find and protect nests on their land, Ms Beech added.

“Technology is allowing us to more easily identify where the curlew is on their land and once they know that [farmers] can adjust.

“That’s usually by agreeing to mow the fields a little later than they may do usually and also create suitable habitats in terms of small wetlands and other important features for curlew throughout the year.”

Natural Resources Wales

Natural Resources WalesMs Beech, who runs a farm herself, said farmers are “keen to help”.

“It’s a species they recognise and it’s part of their culture,” she said.

“We’ve got time [to save the curlew], so now is the time to act so we can ensure that future generations get to hear that fantastic call when the bird arrives back in the uplands in the Spring.”